CI THERAPY. TAUB THERAPY.

Constraint induced movement therapy is one of the neurorehabilitation techniques which has the most scientific evidence to support its efficacy and justify its clinical application.

At the European Neurosciences Center we have professionals who are trained in the USA at Dr. Taub’s unit, which is where this treatment approach was developed.

This publication covers important details concerning this technique to help readers clearly distinguish what exactly CI Therapy is and what it is not.

CI THERAPY. TAUB THERAPY.

INTRODUCTION.

“CI Therapy” or “Constraint Induced Movement Therapy” or “Taub Therapy”, as it is also called, in reference to its creator, is a technique which has been extensively studied, with a large body of evidence supporting its efficacy. This technique was originally designed to increase the functional use of the weaker arm after a stroke and other types of brain injuries. Over the years, other versions have been developed which are focused on the rehabilitation of language problems and the functional use of the lower limb. This technique is used on both adults and children.

Developed by Edward Taub, PhD: https://www.uab.edu/cas/psychology/people/faculty/edward-taub

Edward Taub is a university professor at the Department of Psychology of the University of Alabama in Birmingham, USA. As the Director of the CI Therapy research group and of the Taub Training Clinic. Dr Taub holds a PhD in Psychology by the University of New York in 1970. His work is framed within behavioural neuroscience.

Taub therapy (from now on we shall use the term CI Therapy, the official term recommended by the University of Alabama), derives from behavioural neuroscience research on animals. The theory of learnt non-use and cortical use-dependent reorganization emerged from studies performed on macaws. One of the articles which best explains the animal studies and the development of the theory of learned non-use is the paper entitled “An Operant Approach to Rehabilitation Medicine: Overcoming Learned Non-use by Shaping.”, published in 1994 in the Journal of Experimental Analysis of Behaviour. The full-text is available at the following link:

https://www.uab.edu/citherapy/images/CIT_training/Taub_1994_Shaping.pdf

CI Therapy is currently considered a “family of therapies” which are applied in different manners for the treatment of mobility, functionality and language problems derived by neurological problems and even orthopaedic problems (hip fractures or musician’s dystonia). In the article entitled “Constraint-induced movement therapy: A new family of techniques with broad application to physical rehabilitation- a clinical review.”, published in 1999 in the Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, the clinical applications of CI Therapy are presented in further detail. The full-text is available at the following link: https://www.uab.edu/citherapy/images/pdf_files/citreview_jrrd99.pdf

Finally, to continue studying the origins and foundations of CI Therapy, especially the theories of learned non-use and use-dependent cortical reorganization we recommend the article entitled “New treatments in neurorehabilitation founded on basic research.”, published in 2002 in Nature Reviews Neuroscience, the full-text of this article is accessible at the following link:

https://www.uab.edu/citherapy/images/pdf_files/CIT_review_natreviewneuro030102.pdf

DEFINITION OF CI THERAPY.

- Intensive treatment of the affected limb (or the affected function, for example, in the case of language or gait), which is performed throughout many hours of the day, over 10 consecutive days.

- Training based on a behavioural technique known as shaping.

- Use of a transfer package: these are techniques which promote the transfer of therapeutic gains that occur in the clinic to the patient’s day-to-day, real life situations.

- Prolonged use of a restriction applied to the arm that is not being trained (or other compensatory behaviours).

At this point, two short videos are recommended, available at the following links:

- “CI Therapy for aphasia: regaining the ability to communicate.”: https://www.ycom/watch?v=rwDVsoDQfJQ

- “Remodelling the brain: CI Therapy can change brain structure”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0VYMMJVz3HI

We also recommend readers to view the following video entitled “Neuroplasticity and Healing: A Scientific Symposium with His Holiness The Dalai Lama”, where, after minute 1:32:30 Edward Taub is featured, presenting his studies and experiences with CI Therapy: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zJlmRISL-QA

COMPONENTS OF THE CI THERAPY PROTOCOL.

The application protocol of CI Therapy is conformed of three main components:

- Repeated task-oriented training.

- Behavioural strategies to improve treatment adherence (Transfer package)

- Restriction of the less affected limb.

At this point, it is important to explain what is understood by “restriction” as part of the CI Therapy protocol.

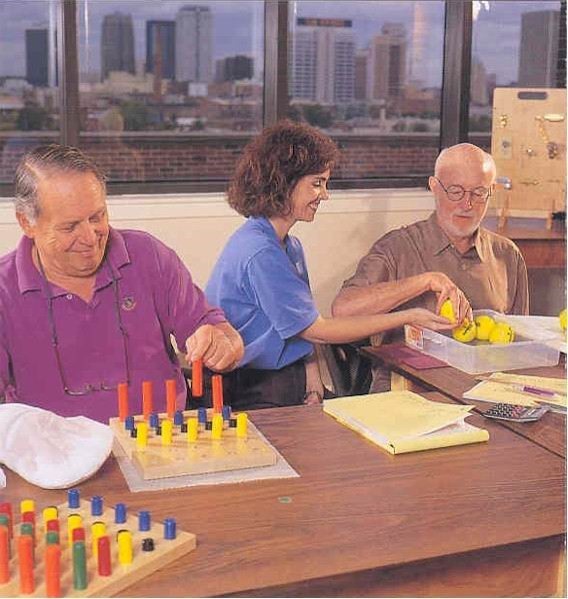

This image shows a patient performing one of the repetitive task-oriented exercises with his left arm, within the CI Therapy protocol for the upper limb. On the right arm, a type of mitt or positioning splint is used which avoids the person from using the less affected arm during the activity. This is considered a “restriction” for the use of the right arm, which forces the person to use the left arm. In the case of this patient, he is being forced to the use the left, more affected arm. This restriction is what most people identify as being the main component of CI Therapy, i.e., the physical restriction of the less affected arm, however, this is the actually the least important aspect. Furthermore, as explained below, the restriction does not only refer to a physical restriction, in this case, via the use of a splint.

Thus, in the treatment protocol developed for the lower limb and gait, the use of the less affected leg is not restricted with any type of splint, or, in the case of CI Therapy applied to language problems (known as CIAT, Constraint Induced Aphasia Therapy), no type of physical restriction is used.

Restriction therefore refers to any action, situation, device or object in the environment, or even belief, which increases or reduces the appearance of a behaviour. Below, we present some examples of restrictions:

- In a patient who wants to stand up from a chair, if we place the less affected leg on a small step and we ask the person to keep it there while he or she stands up: because the leg is higher up than the other, this will force the use of the leg which is on the floor and decrease the use of the leg that is on the step. In this manner, we restrict the use of the less affected leg and force the use of the more affected leg. This is a modification of the environment and of the way the person must stand up.

- In a patient with aphasia, with difficulty pronouncing words, facial expressions and hand gestures are often very helpful for communication, however, they reduce the need for the patient to seek and produce the necessary words. If, during training we were to place a small screen in front of the person to block all visual contact with her, she would have to forcefully produce the words needed to communicate what she wants, without being able to use gestures or facial expressions. In this case, the restriction is the screen, an object in the environment which forces the production of words.

- Another patient has problems for using his right arm (his dominant arm), however he attempts to use it for different everyday actions, such as reaching objects at a table, opening doors, taking clothes from cupboards and drawers, etc. Every time he does so, a family member says: “don’t worry, I’ll give it to you” or “I’ll do it for you”, reaching the objects for him and opening doors for him. In this case, the restriction is the family member who reduces his possibilities of trying to do movements and having his arm participate in daily activities (the family member’s belief is that he or she must do these tasks for him because he is “ill”).

- Lastly, another patient, also with problems in her upper limb, tries to open the doors of her house, cupboards and drawers. However, the doorknobs and drawer handles are small and difficult to manage making it practically impossible for our patient to be successful using her more affected arm, therefore she ends up doing so with her less affected arm. In this case, the restriction is in the environment, in the doorknobs and drawer handles which make the task more difficult by involving the affected arm and forcing the exclusive use of the healthy or less affected side.

Many other examples of restrictions exist which affect the functional use and participation in daily activities of our patients, both with their arms as well as their legs, as well as in cognitive tasks. Speaking of restrictions is in some ways like talking of “barriers” which prevent patients from participating in daily activities. A restriction or barrier can also be used, such as in the case of the splint placed on the less affected arm, to increase the functionality of the more affected arm. What we must identify and correct are the restrictions or barriers which affect the use of the more affected arm, the language production or the use of the lower limbs and mobility in the environment. These barriers must be replaced with “facilitators” of the motor or cognitive behaviour which we seek to improve.

One of the objectives of the CI Therapy protocol is to identify these restrictions and work on them, to improve patient participation and avoid learned non-use.

Continuing with the three main components within the CI Therapy protocol, within each of these, different therapeutic strategies are used:

- Repetitive task-oriented training:

- Massed practice of tasks.

- Behavioural strategies to improve treatment adherence (Transfer Package):

- Behavioural contract.

- Home diary.

- Home skill assignment.

- Daily administration of the MAL (Motor Activity Log).

- Home practice.

- Daily schedule

- Restricted use of the less affected limb:

- Restriction with the mitt.

- Any method that continuously reminds the patient that he or she must use the most affected upper limb (for example, studies are being performed based on the use of sensors).

All these therapeutic strategies are fully described in the article “Constraint-induced Movement Therapy: Characterising the Intervention Protocol.”, published in 2006 in the journal Eura Medicophys, the full text of which is available at the following link: https://www.uab.edu/citherapy/images/CIT_training/constraint-induced_movement_therapy_characterizing_the_intervention_protocol.pdf

THEORETICAL FOUNDATION MODEL: DEVELOPMENT OF THE THEORY OF LEARNED NON-USE

Often, after damage to the central nervous system, for example, after a stroke, which is the neurological illness with the greatest incidence and prevalence, one arm is weaker than the other. During the initial period after damage to the nervous system, the patient may attempt to use the weaker arm, however the result is frustrating and unsuccessful, which means the person eventually stops trying to use it. In the acute phase after a stroke, two main problems occur which affect the mobility of the arm and participation in daily activities: the problem of muscle weakness (the ability to produce enough muscle strength to overcome gravity and the weight of objects which one attempts to move), and the motor control problem (the ability to coordinate the movements of the different joints in order to achieve a specific movement). Some problems may coexist, however, in most studies, it seems like the weakness, in the acute phase, is the main problem resulting in the patient not being able to involve the arm during activities.

All of the above leads to the development of a process of compensation, where the patient successfully adapts based on the exclusive or almost exclusive use of his or her “healthy” or less affected arm, during the performance of daily activities, such as drinking from a cup, dressing grooming, or reaching an object.

This frequent and predominant use of the less affected arm masks the recovery of the more affected arm, meaning that even patients at a later stage have the potential of incorporating the more affected arm in daily tasks, however they have learnt how to not use it, based on the first unsuccessful experiences.

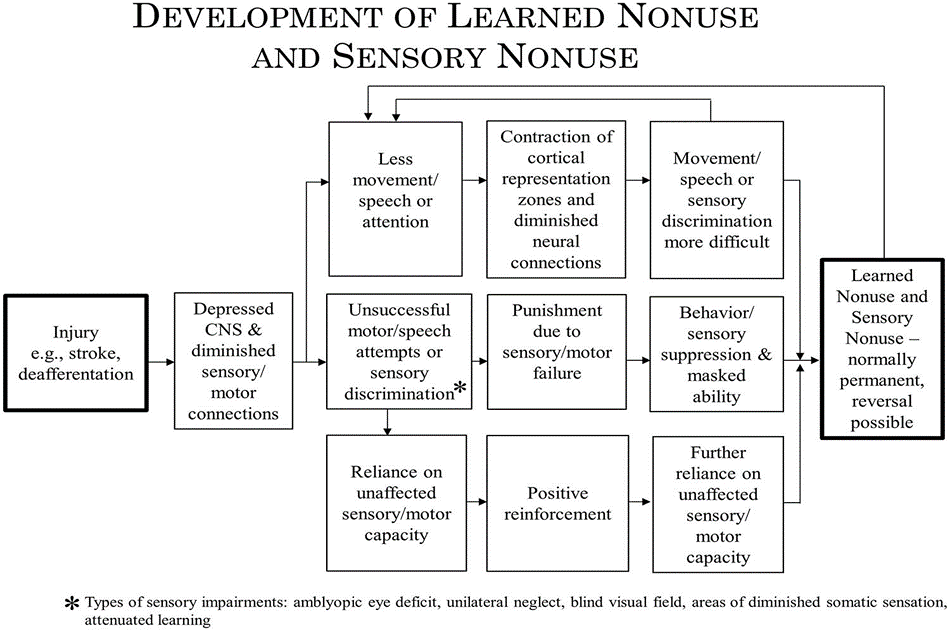

This figure is extracted from an article entitled “Implications of CI therapy for visual deficit training” published in 2014 in the journal Frontiers in integrative Neuroscience. The full-text is available at the following link: ahttps://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnint.2014.00078/full

This article explains how the decreased movement of a limb provokes an alteration of cortical representation and of the neural connections which, at the same time, contributes towards making movement more difficult over time, therefore leading to the development of learned non-use.

The unsuccessful attempts to move the extremity generate a kind of “punishment” based on motor failure, leading to a suppression of the motor behaviour of arm movement, and therefore a masking of any residual capacities, leading to the development of learned non-use.

The dependency on the non-affected capabilities (or less affected capabilities) of the other arm generate a positive reinforcement (because success is achieved when reaching, grasping and manipulating objects) which, in turn, leads to a greater dependency on the capabilities of the less affected limb, likewise contributing to the development of learned non-use.

HOW CAN WE PREVENT OR POSITIVELY INFLUENCE LEARNED NON-USE?

Learned non-use is the term used to describe the failure to use an arm (or a function) spontaneously in everyday life, even when there is potential to be more functional.

The establishment of learned non-use occurs rapidly in conditions such as stroke, however this also develops in another more slow and progressive manner, in other neurological conditions, such as multiple sclerosis, incomplete spinal cord lesion, cerebral palsy, etc.

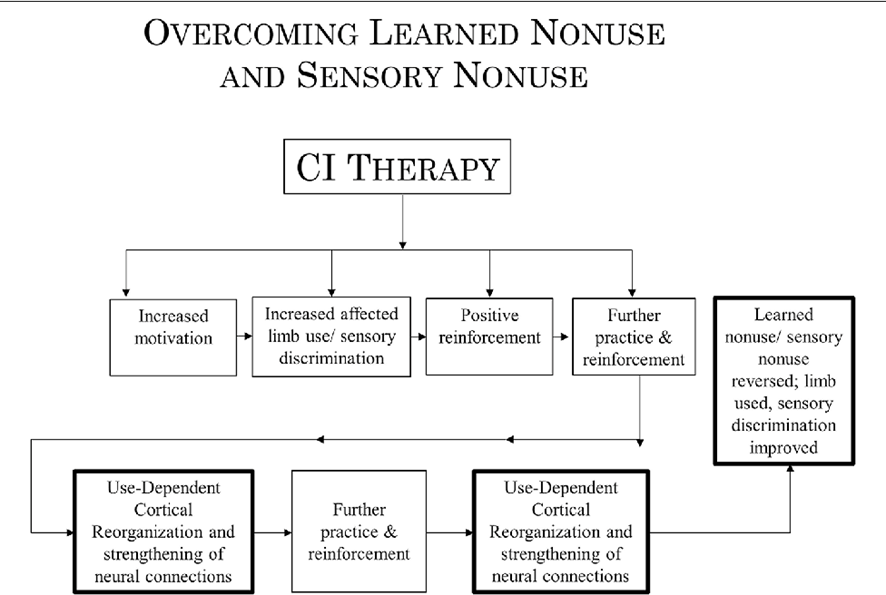

This graph corresponds with the same previously mentioned article: “Implications of CI therapy for visual deficit training”, in this case, it explains how to overcome learned non-use.

CI Therapy encourages patient motivation, increasing the use of the affected limb and improving sensory discrimination, leading to a positive reinforcement which leads to further practice and reinforcement. All of the above implies a cortical use-dependent reorganization and a strengthening of neural connections, which generate more practice and reinforcement, positively influencing and reverting the learned non-use.

At this point, it is important to differentiate between the visible and invisible characteristics of learned non-use. The visible consequences refer to physical appearance, such as:

– deficits in functional activity.

– muscle weakness.

– muscle tension or “spasticity”.

– contractures and limitations of active and passive range of movement.

However, there are also invisible consequences, such as changes in cortical representation and the neuronal connections which form functional brain circuits.

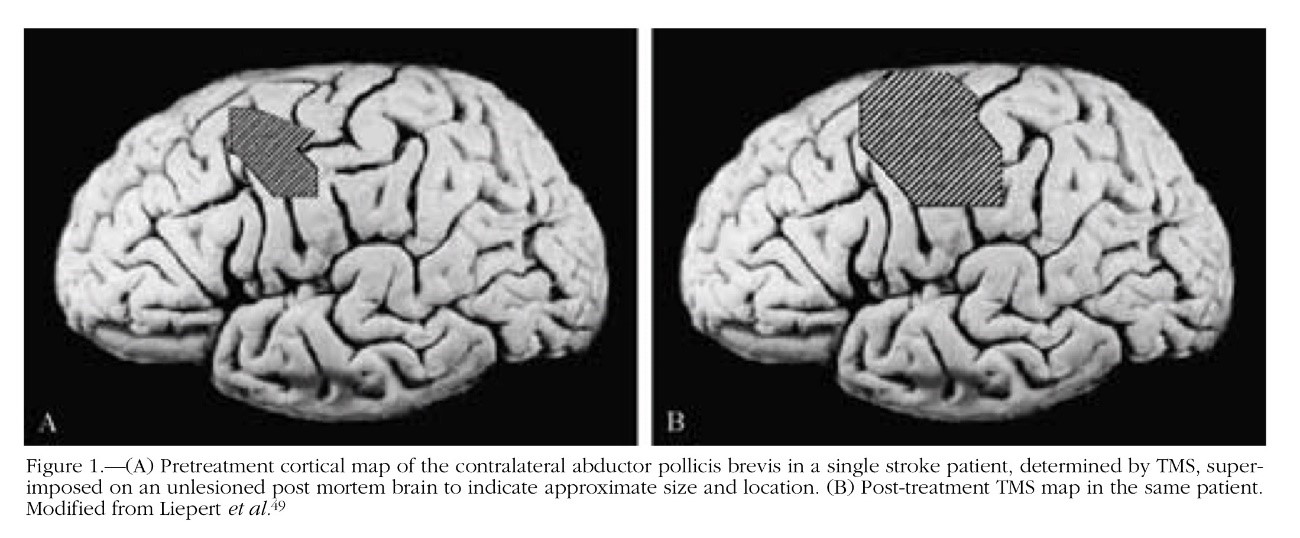

For example, after an injury to the central nervous system, such as a stroke, the area of cortical representation of the affected arm tends to “shrink”, reflecting the lack of use of the weaker arm and reinforcing the cycle of learned non-use. This process can be consulted in the article entitled Treatment-Induced Cortical Reorganization After Stroke in Humans published in the year 2000 in Stroke. The full-text is available at the following link:

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1161/01.STR.31.6.1210

Several studies on CI Therapy have attempted to objectify the changes that occur, not only on a behavioural level (increased movements, participation in daily activity), but also at the level of brain structures and neuronal connections. This is highlighted in the paper Neuroplasticity and Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy published in 2006 in Europa Medicophysica. The full-text is available at the following link: https://www.minervamedica.it/en/journals/europa-medicophysica/article.php?cod=R33Y2006N03A0269

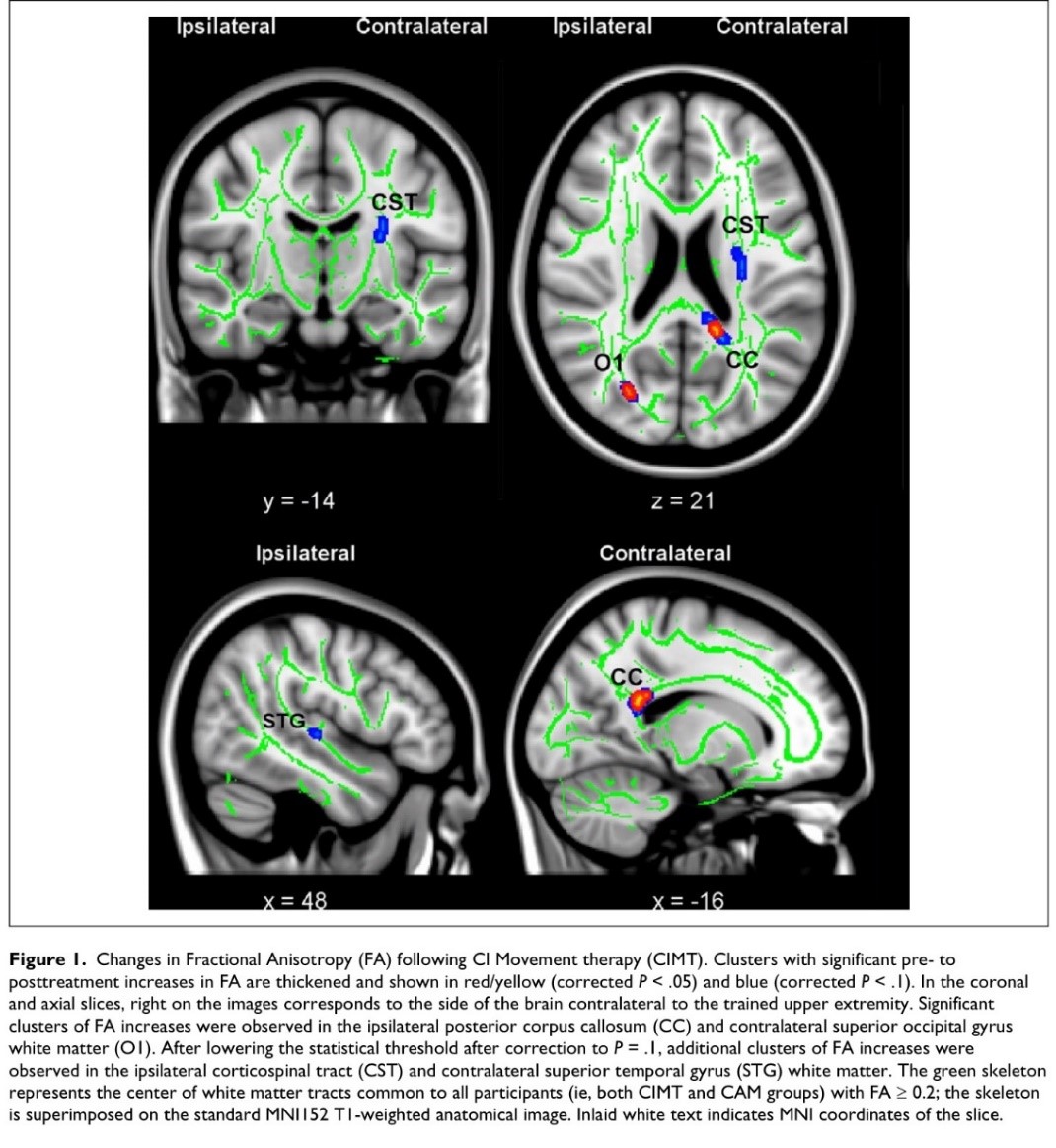

- Many articles have been published on the changes in the central nervous system that occur after a CI Therapy intervention, and each year new studies are published. Therefore, we shall not go into further details on this subject, as the reader can continue to read about this technique, by conducting a simple database search. To conclude, we would like to share one more example which we find inspiring. A randomized clinical trial was performed on the use of CI Therapy in people with multiple sclerosis. This study consisted of two parts, one, focused on objectifying the changes that occur on a functional level, on real activities of daily living, and another, based on objectifying the changes that occur in the integrity of the white matter.The first of these, entitled “Phase II randomized controlled trial of CI therapy in MS. Part I:Effects on real-world function”, published in 2018 in Neurorehabil Neural Repair can be consulted at the following link: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5978742/pdf/nihms939864.pdfThe second, entitled “Phase II Randomized controlled trial of CI therapy in MS. Part 2:Effect on white matter integrity” published in 2018 in the same journal, Neurorehabil Neural Repair is available here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5912693/pdf/nihms929451.pdf

- CHARACTERISTICS OF CI THERAPY

- Focus of intervention on function.

- Focus of intervention on the transfer of learning to the patient’s real environment.

- Importance of massed and concentrated practice.

- Shaping and Task-Oriented Training as treatment techniques.

- Use of strategies to improve treatment adherence.

- Focus of intervention on function:

- More attention to activity and activity limitations (according to the terms used in the ICF, the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: https://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/ )

- Less attention to deficits (“Body structures and functions”, also based on the ICF terminology).

- Furthermore, the quality of movement is considered (not ignored). The quality of movement is treated via “hands off” strategies, where modifications to the task and the environment influence the patient’s execution, compared to other forms of treatment based on “hands on” strategies, where physical facilitation is used by therapists to attempt to provoke changes in the quality of the patient’s execution. We use the term “attempt” because, at present, these techniques have not demonstrated their theoretical affirmations in clinical trials, in other words, they lack solid scientific evidence.

- Focus of the intervention on the transfer of learning to the patient’s real environment.

- Emphasis is placed on the function, in the environment of the patient’s home/community.

- The activities outside the clinic are just as important (if not more) than those performed in the clinic.

- The patient is asked to keep a record of the treatment activities.

- Motor problem solving is emphasized during the intervention.

- Importance of massed and concentrated practice.

- The repeated use of the more affected extremity is encouraged (or of the function).

- For many hours every day.

- Over several consecutive days.

- The original protocol was based on 6 hours a day in the clinic + home tasks. Currently, this protocol has evolved to 4 hours in clinic + home tasks, which can take around 1 to 2 hours.

- In the modified protocol, the number of hours of clinical and practice is reduced, based on 3 hours in the clinic and 1 hour at home.

- This protocol is performed during two consecutive weeks, from Monday to Friday, and on weekends rest periods are allowed.

- The repeated use of the more affected extremity is encouraged (or of the function).

- Shaping and task training as treatment techniques.

- Task oriented treatment; Activity based therapy.

- Emphasis on the use of the more affected limb (or the more affected function).

- The treatment is performed systematically (a protocol exists which guides the intervention. The protocol does not mean that the same thing is done for every patient, each treatment is adapted to the patient’s deficits and capabilities).

- Specific interactions take place between the participant and the interventions. In the case of upper limb training, different categories of patients are specified, according to their ability to move the wrist and fingers, determining the treatment path for conducting the intervention.

- Use of strategies to improve treatment adherence.

- The different components of the “transfer package” are used repeatedly and consistently to improve patient’s self-efficacy and responsibility towards treatment.

- For example, the MAL is used on a daily basis (Motor Activity Log: https://www.uab.edu/citherapy/images/pdf_files/Cpdf ) this usually means an increase in the activities that the patient performs outside the clinic, as it is like a small “exam” which the patient must go through daily.

- By signing a behavioural contract, a commitment is made concerning the performance of certain activities, which means an increased responsibility of the patient towards therapy.

- The different components of the “transfer package” are used repeatedly and consistently to improve patient’s self-efficacy and responsibility towards treatment.

- In addition, a form is used for recording the tasks done at home, which is updated and revised each day between the patient and the therapist, and which means an increased self-efficacy in the performance of the agreed activities. Every day the patient must record wither or not he or she has done the agreed activities, how long these were performed, and observations regarding performance.

- RESEARCH SUPPORTING THE USE OF CI THERAPYThe number of studies and clinical trials based on CI Therapy has increased over the last 20 years. A simple Pubmed search reveals an increase in the number of papers published from 1997 until present (for example, using the search terms “constraint induced movement Therapy” or “constraint induced movement Therapy stroke”).When we analyse the evidence available based on scientific studies of CI Therapy, undoubtedly, this is one of the interventions with the best evidence. This technique is recommended in the best and most important clinical practice guides, meta-analyses and systematic reviews.We recommend the following articles, which are just some of the most important articles on the subject:

- “Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy after Stroke”, published in 2016 in Lancet Neurol. The full-text of this article is available here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4361809/pdf/nihms655812.pdf

- “Constraint-induced movement therapy in treatment of acute and sub-acute stroke: a meta-analysis of 16 randomized controlled trials.”, published in 2017 in Neural regeneration research. The full-text of this article is available here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5649464/

- “Effect of constraint-induced movement therapy on upper extremity function 3 to 9 months after stroke: the EXCITE randomized clinical trial.”, published in 2006 in Jama. The full-text of this article is available here: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/203876

This latter article, which refers to what is known as the EXCITE trial (Extremity Constraint Induced Therapy Evaluation), represents one of the most important studies within CI Therapy. This was a multicentric study (7 different hospitals), with a randomized controlled design, featuring patients in the subacute phase (3-6 months) and chronic phase (6 to 12 months) of the disease. The study took place over 5 years, with a sample of 222 participants, and including a 2-year follow-up to evaluate the results were maintained. Therefore, this is an important study which is worth reading closely.

Of all the studies performed on CI Therapy, most refer to the upper limb and patients with stroke, however many other pathologies have been researched, especially cerebral palsy, multiple sclerosis (especially in the last years) traumatic brain injury, and also, especially in recent years, studies on the application in aphasia (CIAT, Constraint induced aphasia Therapy) and in training of lower limbs and gait.

To cite a few articles of reference in these other fields of application of CI Therapy:

- “Constraint-induced aphasia therapy in post-stroke aphasia rehabilitation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.”, published in 2017 in PLoS One, with the full text available t: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5573268/pdf/pone.0183349.pdf

- “Effectiveness of constraint-induced movement therapy on upper-extremity function in children with cerebral palsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.”, published in 2014 in Clinical Rehabilitation and available at the following link: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0269215514544982?rfr_dat=cr_pub%3Dpubmed&url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori%3Arid%3Acrossref.org&journalCode=crea

- “Effects of constraint-induced movement therapy for lower limbs on measurements of functional mobility and postural balance in subjects with stroke: a randomized controlled trial.”, published in 2017 in Top Stroke Rehabilitation and available at the following link: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10749357.2017.1366011?journalCode=ytsr20

Lastly, we recommend the following video entitled “The Research Behind CI Therapy”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7VqfGTLIp88&list=PLz_WMXyN3CKjNS9RWETBU9yQsRhr3x-Jd&index=2&t=0s

This video is by Lynne Gauthier, one of the most important researchers in CI Therapy: https://www.linkedin.com/in/lynne-gauthier-b5023724/

In the same YouTube channel we can find other very interesting videos on different aspects of CI Therapy:

- “CI Therapy Transfer Package”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dlwk5uV3gKY&list=PLz_WMXyN3CKjNS9RWETBU9yQsRhr3x-Jd&index=2

This video explains the importance of the transfer package, which, in the words of Edward Taub, is the most important part of CI Therapy treatment. To increase the information on the transfer package, readers may also consult the following article: “Method for enhancing real-world use of a more affected arm in chronic stroke: transfer package of constraint-induced movement therapy.”, published in 2013 in Stroke. The full-text is available at the following link: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3703737/pdf/nihms462417.pdf

- “CI therapy Frequently Asked Questions”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gsk5CRhadVg&list=PLz_WMXyN3CKjNS9RWETBU9yQsRhr3x-Jd&index=3

The above link answers typical questions on what types of patients can participate and when is the most appropriate time to apply this kind of therapy, among other questions.

- Caregiver Tips: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t4JOP9hv1_o&list=PLz_WMXyN3CKjNS9RWETBU9yQsRhr3x-Jd&index=5

Caregiver tips, responding to classic questions made by family members and caregivers, when a family member is undergoing a CI Therapy program.

- “CI therapy through gaming”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GulkDOQ_z48&list=PLz_WMXyN3CKjNS9RWETBU9yQsRhr3x-Jd&index=4

Here, the use of a videogame is explained (https://gamesthatmoveyou.com/about) which, via a telerehabilitation platform, attempts to reach patients who cannot benefit from a CI Therapy program in the clinic.

CI THERAPY AT THE UNIVERSITY OF ALABAMA

We recommend readers to visit the website of the CI Therapy unit, within the department of Psychology of the University of Alabama at Birmingham: https://www.uab.edu/citherapy/

Here you may find information on:

- The treatment unit for adults: https://www.uabmedicine.org/patient-care/treatments/ci-therapy

- The treatment unit for children: https://www.childrensal.org/default.cfm?id=1

- The aphasia treatment unit: https://www.uabmedicine.org/patient-care/treatments/ci-therapy

- The training courses that are performed in Birmingham, Alabama: https://www.uab.edu/citherapy/reaseach-training

- Manuals on assessment tools which the team have developed and use, and other publications: https://www.uab.edu/citherapy/training-manuals-a-publications

The Association of Intensive Therapies in Neurorehabilitation (TIN), registered in Spain, are organizers of the first official CI Therapy training courses organized in Spain, with one of the main developers of the technique, Dr. David Morris: https://www.uab.edu/shp/pt/people/faculty/david-m-morris

THE FUTURE OF CI THERAPY

- Use of new technologies for the assessment and treatment of patients involved in a CI Therapy protocol. The use of tele rehabilitation as a complement to therapy, to increase patient practice.

- Use of sensors to register the use of the more affected upper limb and increase the use of the same via reminders in the form of mobile phone messages or small vibrations to the wrist (as an alternative to the restriction of the more affected arm).

- Measurements of changes at the level of the brain via the study of functional brain networks (conectoma).

- Development of enriched environments in CI Therapy protocols to increase the use of the affected function (whether this is the arm, the leg or language).

- Development of training programs for patients with severe disabilities (studies on this subject, known as Expanded CI Therapy have already began (https://content.iospress.com/articles/restorative-neurology-and-neuroscience/rnn170792)

For further enquiries regarding this publication or to arrange an appointment please contact us at the numbers below:

European Neurosciences Center

Avenida de la Osa Mayor 2, 28023 Madrid, Spain.

Telephone number: +34 917370557

Mobile telephone number and Whatsapp: +34 686528717